A collective sigh rings out at this time of year from educators at all levels. That relief is a sure sign that our teaching and learning environments are toxic. The negative reinforcement that accompanies our escape from the classroom prompts a wide variety of utterances that are symptomatic of that toxicity, but which are also red herrings. We wail and gnash our teeth when parents challenge carefully considered student evaluations; we despair when administrators fail to support us and change grades unilaterally. We moan and groan over our own annual evaluations and the amount of energy spent collecting supportive data for them. We fume at the excessive standardized testing required of students and the time we spend proctoring. We throw up our hands in dismay when union leadership appears too willing to accept corporatist ideals.

What we seldom do is consider the root causes of our dismay and discouragement. We hope that temporary escape from these various symptoms will cure the underlying disease. Unless we confront our demons, we simply return in the fall and repeat the cycle. Each passing year breeds further alienation from the institution we once cherished.

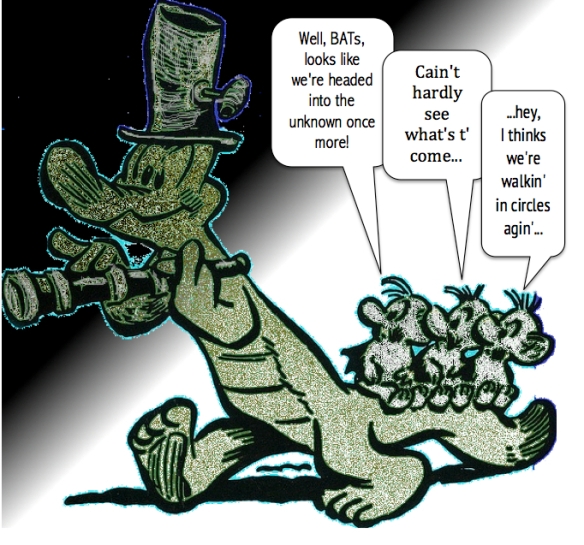

We are walking in circles. All of the hubbub concerning CCSS (including the hubbub emanating from this site) and the anger against Bill Gates, the Kochs, etc.–is hot air unless it results in an ongoing reconsideration of all public educational policies by professional educators at all levels.

The inclination teachers have to carp about the complaints students and parents make about grades is more a symptom of loss of power and dignity than it is a comment about student performance or behavior. Likewise, the complaints we make about “harvesting student growth data” or administering standardized testing has less to do with either task than it does the corruption of a supportive student/teacher relationship. When we focus on these symptomatic issues, we allow these tangential problems to distract us from what is most important, and we continue on our circular route.

Attacks on union leadership in education also distract us from more important issues. We look to NEA and AFT leadership to challenge the rush to corporatism in education, and when their efforts seem timid, we assume they must be cozy with corporate deformers. To be blunt: do some union leaders receive compensation that is excessive? Do they not represent teachers but instead front a corporatized entity that pretends to represent us? Perhaps, but the stated purpose those leaders serve is to improve workplace conditions, pay rates and benefits to rank and file members so that those workers can focus on student needs. Vote ’em out if they aren’t effective in these areas. Compare that purpose to the goal of CEOs in private corporations − maximizing returns to stockholders. Consider the amazing inequalities of income and benefits that exist between executives in private companies and their workers, and ponder the fact that those companies thrive on that exploitation. We have little to complain about. Focus on the bigger issue, and deal with the little fish at election time.

The root issue—the underlying disease– for educators today is an excessive and often abusive reliance on evaluation measures that strip both teacher and student of dignity and power. Corporatists honestly believe that defining goals and measuring progress toward them−a practice that serves well when manufacturing consumer goods− ought to provide a solid foundation in the educational world as well. We can restore dignity and render the issue of power moot by demanding reconsideration of the role evaluation ought to play in the educational environment.

I’ve given my share of grades to students, and I’ve never felt productive or positive when doing so. Students who are just beginning to comprehend the basics of a discipline do not need categorization− they need support and encouragement. Students who are at advanced levels in study do not benefit from microanalysis of their performance− they benefit from reflection on their practice with the input and advice of established experts. Take it closer to home– we do not provide a significant other with an evaluation of their performance according to a set of proficiency standards. Why not? We inherently sense the inappropriateness of judging the performance of a loved one according to a set of external standards. Why do we view the appropriateness of evaluation for learners any differently? We should stop now.

How do you feel as a professional when you sit down with an administrator to find out whether they have labeled you as “Distinguished,” “Proficient,” “Developing,” or “Below Expectations?” Do you feel emboldened to push into new areas of pedagogy and curricular development? Or do you feel relieved that your paycheck is safe for another year? We put students through this experience regularly, and we have no evidence that they − or us−are better people or learners for it.

Evaluation is not a necessary part of learning. It is, at best, a number or letter external to the learner’s personal experience. It is a means of quantifiable coercion at worst. It is unproductive and unnecessary.

John Lennon’s song, Imagine, represents the challenge in front of us. We take the first step toward freedom of mind and spirit when we begin to imagine alternatives to our own history. Imagine there’s no report card; I know it’s hard to do− Imagine all the students learning; learning for themselves… That is the relationship I envision between my students and myself, and I’ve long wondered why it doesn’t exist.

And now I know. The corporatist vision demands absolutes. Evaluation is a natural and necessary part of their absolutist domain, and they demand we participate in that world. They prescribe standardized tests and Danielson rubrics to ensure that we do participate.

I prescribe abstinence. I prescribe the unknown and unfamiliar.

It’s wise to venture into the unknown if you do so with a sense of purpose and a sense of direction. But please, reconsider both that purpose and your direction from time to time; don’t just walk in circles.

That’s the difference between adhering to standards and using standards as a framework for professional judgment.

© David Sudmeier, 2014

A thoughtful, well integrated piece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. However, like almost ALL educators, you are very good at preaching to the choir. Your ideas will have little impact until they show up in the major media. Sad. Maybe you could publish a book? Being a Guest on Bill Moyers show does not count, unfortunately. Just my opinion. Thank you anyway.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Took me a while just to fill the soprano section, so I’m pleased to have a choir of any sort. A book? Hmmmm…happy to, but so far no nibbles. Bill Moyers doesn’t count? Yikes! You set a high bar, man… ; )

LikeLike